Undoubtedly, the European "symbolic geography", or "imaginary geography",1 still nurtures a vision of "better" and "worse" Europe. At the turn of the 19th century, such was the overriding conceptual paradigm espoused by the intellectual and political elites of Western Europe. The prevalent representation of Europe that -came into being at that time was based on the dichotomously constructed concepts of culture, civilization and progress underpinned by the us/them division. The discourse and its strategies relied heavily on the value-laden opposition between the dominant centre (us) and the troublesome periphery (them).2 In this system, Western Europe (in its West-and-North variant) connoted progress, civilisation, culture, urbanisation, pragmatism, rationality and, hence, a "good" coloniser – a Kulturträger carrying White Men's Burden3 (The Burden of the Balkans, Durham 1905)4 – who disseminated civilisation and values. The Balkans (with its opposite East-and-South marking) in "the colonial reading" were synonymous with obsolescence, stagnation, backwardness, superstition, despotic leanings, and recoil from advancement, all of which made them inevitably liable to absorb "genuine" values from abroad. As Bulgarian-born (i.e. Balkan-born) Julia Kristeva puts it, the Balkans became "disturbingly strange", "the otherness to our ourness",5 alien to our (European) identity.6

The processes in which negative, stigmatising labels were produced and perpetuated (also by the literature of the "civilised" countries) – or, in other words, the rise and spread of "imperialism of imagination" – has been insightfully analysed by many Balkan imagologists. Seminal studies addressing this theme were written by Maria Todorova,7 Vesna Goldsworthy,8 Božidar Jezernik,9 Jelica Novaković-Lopušina10 and many others.11 They imply that the pronounced role of the Balkans as "the Other" of Europe coincided with the onset of the continent's ideological preoccupation with the discourse of modernity and civilisational advancement. The neutrality of geographical denotation (the Balkan Peninsula) receded then, pushed aside by the intrinsically political connotations of "barrel of powder", "Balkan melting pot", "fracture zone", "Europe's heart of darkness", or "wild Europe" to name but a few, still commonly used, coinages.12 The analyses of imagery featuring in the texts of Western travellers and other experts on the Balkans (diplomats, historians, politicians) between the 16th and 20th centuries indicate that their accounts were, perforce, highly reductionist. They heavily relied on the mediation of translators/interpreters since the Western travellers did not speak the indigenous languages. Consequently, their observations are framed by stereotyped expectations they projected on the realities they saw, and as such are, recognisably, vehicles of mental colonisation. Though the mental colonisation proceeded without actual territorial conquests, it was indubitably a struggle for the readers' souls and minds, in which the charting of symbolic maps of the imagination served as a major weapon. In the many accounts which portray the mythologised, or even demonised, Balkans, researchers expose the whole "anatomy" of stereotypes informed by the us/them principle actively at work in the texts' imagery. If read in the post-colonial theoretical framework, the texts reveal an old (but in many cases still valid) traveller perspective as a kind of a symbolic mirror which reflects not only the alien culture, but first of all the traveller's own one. As a rule, the texts served to perpetuate stereotypes and validated the traveller's superiority to the nations and regions s/he described. The travellers' depictions evaluate "unemancipated" and "primitive" cultures, exerting thereby control over the incomprehensible Other, whose exotic, ruthless or, sometimes, "vampirical" nature was deeply unsettling.13 In this way, literary and paraliterary texts (e.g. travel reports or travel journalism) contributed to the negative Balkan "imaginarium" – a symbolic "map of the imagination" that pictured South-Eastern Europe as perceived by the inhabitants of Western Europe.

Rebecca West's Personal Map of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The development of Western knowledge about Yugoslavia and the Balkans received a major thrust from Cecily Isabel Fairfield (1892–1983), a British author, journalist, feminist activist and literary critic, commonly known as Rebecca West.14

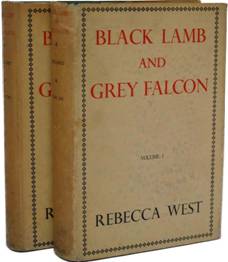

Her monumental work titled Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. A Journey through Yugoslavia published in two volumes in the autumn of 1941 in the USA (and a few months later, in 1942, also in Great Britain) has since proven an important point of reference on the symbolic map of Western-European representations of South-Eastern Europe. Its impact was most powerfully felt twice: first, during World War Two, when the book was launched, and in the 90s of the 20th century when socialist Yugoslavia fell apart in a bloody carnage. I would like to outline three diverse stages of charting, i.e. extrapolating this book onto the audience's "map" of consciousness, which corresponds to the production of a specific map of symbolic geography. Two initial stages pertain to the Yugoslavian, or broadly speaking Balkan, discourse and its perception by the West (one of them is Rebecca West's own and anti-colonial, and the other – affected by Rebecca West's text and the current political conjuncture – is marked by colonial attitudes). Both of them were coterminous with wartime: the first took place during World War Two, and the second during the decomposition of Yugoslavia. The third stage of charting Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, not particularly pronounced yet, might consist in the post-colonial reading of West's book currently – in the early 21st century with its relatively peaceful and stabilised political situation. It could render a balanced analysis (and actualisation) of Rebecca West's text, free from the moment-induced emotional vicissitudes. As such, it could facilitate a fair assessment of her abundant observations and offer an opportunity of proposing their "own (small) narratives" to the independent nations, which are rising back from the rubble of Yugoslavia liberated from the imperative of spinning a grand, unifying (Yugoslavian or Balkan) narrative.

In this survey article my purpose is to focus primarily on how Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. The Journey through Yugoslavia worked when it was first published, that is, on how the book with its inherent anti-colonial message contributed to the formation of the Yugoslav imaginarium in its English language-speaking audience. Subsequently, I briefly show whose perception of Yugoslavia was directly affected by Rebecca West's book in the 1990s, when the region attracted enhanced attention. And finally, I cursorily sketch meager (so far) reception of the book in the post-Yugoslav countries. In the concluding part, I only postulate that this nearly blank page should be inscribed by the representatives of the nations depicted in Rebecca's West monumental work. This post-colonial reading of the book might prove the most inspiring one and illuminate the essential dimensions of the dialogue among cultures and national identity issues in the region described by Rebecca West. This third charting must however commence intra muros, that is, within particular cultures because that only could render a mosaic of perspectives. The proportions of my presentation of the charting stages of the book in this article must perforce be uneven, because circumstantial evidence palpable traces (articles, books, commentaries or analyses) are the scarcest in the case of the third-stage reception. This article aims fundamentally to signal the contemporary, as yet not fully enacted, potential of Black Lamb and Grey Falcon.

Three Stages of Charting of Black Lamb and Grey Falcon by Rebecca West

First Charting: World War Two – Gone with the Balkans

Rebecca West's attitude, undoubtedly a species of the Western Orientalist discourse, has had a major impact on the perception of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in the English-speaking culture. Hers is the first and, so far, the most compendious book (1150 pages plus) devoted exclusively to this part of the world.15 More than 70 years after it was first published, it is still regarded as one of the best sources of knowledge about the territory, its inhabitants, culture and customs. The American journalist Robert Kaplan, who authored Balkan Ghosts: A Journey Through History in 1993, called West's book "this [20th] century's greatest travel book".16 Victoria Glendinning, West's biographer, assesses the Balkan book as the author's perennial work,17 her opus magnum, which influenced her post-war writing (including such texts as the novel The Meaning of Treason, 1948, and The Birds Fall Down, 1966).

Unprecedented and unparalleled in the Western world, West's fascination with Yugoslavia and the Balkans was initially a pretty coincidental effect of her love for travelling as such and her collaboration with the British Council. In 1935, the writer went to Scandinavia to deliver a series of lectures commissioned by the British Council. Her literary and journalist interests were then focused on, to use her own words, "small nation[s] threatened by the great powers" and struggling, nevertheless, for independence and sovereignty.18 Her initial project was to write a book about Finland, because among the countries she visited on her trip to the North, it fully met the above criteria. And yet, when one year later the British Council commissioned her to go on a lecture tour to the Balkans, West realised that the then Yugoslavia (in the late 30s of the 20th century) was a far more interesting and multifaceted example of ideas she wanted to address in her book than Finland. As it turned out later, it was her journey to Yugoslavia that provided a kind of epiphany, a political-historical-cultural revelation which was to prove a decisive factor in shaping her future views. In the epilogue, she wrote: "Nothing in my life had affected me more than this journey through Yugoslavia. […] [M]y journey moved me also because it was like picking up a strand of wool that would lead me out of a labyrinth in which, to my surprise, I had found myself immured".19

Black Lamb and Grey Falcon is the fruit of West's three trips to the Balkans and her later studies on the region, the impressive scope of which is suggested by the rich bibliography attached to the book, featuring sixty selected (as she indicated herself) entries. The first trip, organised by the British Council, took place in the autumn of 1936. Without learning about the region by way of preparation, West visited a few Yugoslavian towns on a lecture tour. On her second trip in the spring of 1937, she was accompanied by her husband Henry Maxwell Andrews, a British banker, with whom she tried to share her fascination. Before that journey, however, she had read a number of books and purposefully sought knowledge about the region. She went to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia for the third time in the summer of 1938 in order to compile additional materials for her "an unendurably horrible book to have to write" as she put it.20

The monumental work consists of a prologue, ten voluminous chapters and an epilogue of 80 pages. It is a hybrid text combining elements of travel report, journal, autobiographical notes, novel, and philosophical-sociological essay. It astonishingly and impressively (though also controversially) interweaves fact and fiction, traverses the intersections of history, archaeology, politics, folklore, mythology, ethnography and culture in the broadest sense of the term, and offers a multiperspectival array of the author's personal views on religion, ethics, art and gender. Occasionally, the book is compared to the Bible not only because it approximates the Scripture in size, but also because it similarly invites endless readings and re-readings, revealing new layers of meanings in each encounter. At the same time, West's book on Yugoslavia engages in an interesting interpretation of European politics of the late 30s of the 20th century, passing thereby many severe judgments. Throughout the enterprise, the author demonstrates rare skills of synthetic reasoning. "She perfectly grasped the cause-effect relationships among the past, the present and the future as well as the major directions of historical development".21 Additionally, she resorted to nostalgic rhetoric (which was one of the targets of criticism, actually) to construct analogies between the history of Yugoslavia and its myth on the one hand and the wartime crisis in Europe on the other. In her subjective approach to the past, she cherished an idealised vision of the state of the Southern Slavs22 and treated the Balkan history symbolically and allegorically.23

Even at the moment of publication, West's book stood out among earlier, Orientalist commentaries offered by other British writers. The main difference lay in that the image of the Balkans it produced was at odds with the prior negative renderings, and its diction diverged from the patronising tone ubiquitously adopted in earlier English writings on the Balkans. The writer did not uphold the us/them, centre/periphery, "better" Europe/"worse" Europe division. Instead, in an "anti-colonial" mode, she unified the map of Europe, emphasizing that the Balkans not only were a legitimate part of the Old Continent, but also had greatly contributed to it. "I became newly doubtful of empires," she wrote, "the South Slavs have also suffered extremely from the inability of empires. (...) The contemplation of Yugoslavia suggests other, and catastrophic, aspects of Empire. (...) It is certain that the Balkans lost more from contact with all modern empires than they ever gained. They belonged to the sphere of tragedy, and Empire cannot understand the tragic".24 She also highlighted the Balkans' sacrificial role as "the Bulwark of Christianity", yet her handling of the well-known trope was novel in that she shifted the traditional border of Antemurale Chrisianitatis eastward – beyond the Catholic countries (Croatia, Slovenia) onto the Orthodox Macedonia and Serbia. In the face of the ongoing struggle against Fascism (let's keep in mind that the book was written when Nazism was rife and rampant in Europe), in the epilogue she exhorted the Western countries to draw on South-Eastern Europe's historical experience in putting up a fight against empires. West outlined an extremely vivid, opulent, mosaic-like map of the Balkans, which was both attractive and complicated. Although enthusiastic about the royal (first) Yugoslavia, she managed to steer clear of gross simplifications.

Such an appealing rendering of the Slavonic South was most likely influenced by Stanislav Vinaver (1891–1955), a Serbian writer of Jewish origins (which West repeatedly stresses), translator, polyglot, and intellectual. The then official of the Ministry of Information was West and her husband's guide and travel companion. West met also other intellectuals – Vinaver's friends and acquaintances – such as bishop Nikolaj Velimirovic (1881–1956) or, in Macedonia, Anica Savić-Rebac (1892–1953), a Serbian philosopher and classical scholar, and her husband Hasan Rebac (1890–1953), a Herzegovina-born Muslim and a graduate of Sorbonne's Oriental Studies. These and other real people materialise in the book concealed as fictitious personages: Stanislav Vinaver appears as Constantine; his German wife Elsa is Gerda, whom West constructs as an obnoxious figure embodying all negative features West thought typical of the German element; and Anica and Hasan Rebac are pictured in Militsa and Mehmed. As the book was published in wartime, when Yugoslavia had already found itself under the Nazi occupation, West did not want to put many well-known and easily recognisable people in jeopardy and, therefore, changed her Serbian friends' names, though, admittedly, the fictional names were far from indecipherable. That she was fully aware how hazardous the exposure could be for them can be inferred from the book's dedication: "To my friends in Yugoslavia, who are now all dead or enslaved. Grant to them the Fatherland of their desire and make them again citizens of Paradise".25

West supported the monarchic Yugoslavia of the interbellum period since she was attracted to the idea of a commonly shared state of Southern Slavs, which could bring together multiple cultures, ethnicities and religions. Importantly, she saw this arrangement as a new conceptual pattern for Europe to imitate, which postulate is explicitly reiterated throughout her compendium. Confronting the challenge posed by the rise of Fascism in the 30s as well as witnessing its culmination in World War Two, she championed the vision of Europe as a unified whole, undivided by any ruptures, and united by common, mutual responsibility. In this enterprise, she propounded the history of the Balkans/Yugoslavia as a lesson to be absorbed by Europe, which could learn from the Balkan countries' centuries-long endeavours to resist the imperial ambitions of the Ottomans, the Habsburgs and the tsarist Russia and sustain their identity throughout ages of political dependence. She saw in them a historically corroborated model of relationships between the empire and small nations, in which the process of regaining independence went on painstakingly but surely. In the epilogue, she wrote: "I became newly doubtful of empires. Since childhood I had been consciously and unconsciously debating their value, because I was born a citizen of one of the greatest empires the world has ever seen, and grew up as one of its exasperated critics.26 She saw both Fascism and Communism of the 30s as new imperial threats Europe had to confront.

I believe that West's change of mind about the title of her opus magnum is telling. The first intended title was Gone with the Balkans, and it was only towards the end of her work on the text that West decided to title it Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. The choice of the eponymous (Macedonian and Serbian) sacrificial symbols suggests that the author's attitude and concept of how the work was to be interpreted had changed and signals that her priorities had altered. The original title – an evident reference to Margaret Mitchell's bestselling Gone with the Wind from 1936 – was most likely intended to underscore that the book preserved the world which no longer existed. It was, we shall remember, 1941: a bleak time of World War Two, bombings of London, occupation of Yugoslavia, when the Nazi darkness seemed to envelop the whole of Europe relentlessly. With Belgrade destroyed in air-raids and Yugoslavian territories, which West had visited but a few years earlier, lying waste, the lot of royal Yugoslavia was uncertain, though it was not obvious yet that it was destined to disappear. The actual title highlights the symbols of the cult of sacrifice – images of a black lamb27 and a grey falcon featuring in the epic poem Propast carstva srpskoga ('The fall of the Serbian empire').28 Thereby, West on the one hand foregrounds the role of Macedonian and Serbian cultures in her reading of the Balkans, and on the other seeks to challenge the Christian idealisation of pain, suffering, defeat and death that permeates European tradition. This polemical investment is clear in the epilogue. Against the backdrop of old Slavic symbols, West conjures up a current vision of the Battle of England alongside the fascist threat and urges her British and American readers to actively take up arms against Nazism. She encourages them to abandon the posture of a victim and build up salubrious nationalism.

When the bulky volume (1150 pages!) was published – in the deprived times of war, when paper was rationed29 – its political message and historical-cultural analyses counted as its great assets. The 80-page-long epilogue proved then the most interesting to the British readership. As it was repeatedly stressed, it was a perfect example of the most skilful war propaganda ever written.30 This was patently the role the book fulfilled (alongside its informative function) in its first reception wave.

We could also add that the book elicited animated, but also often critical, responses from the members of the populous, nationally diversified Yugoslavian wartime diaspora in London,31 with Stojan Pribićevic adding probably the most important voice to the discussion.32

Second Charting: The 90s of the 20th Century

The second extrapolation of Rebecca West's book onto the symbolic literary map of Europe took place in the 90s, when in a bloody clash the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia disintegrated into nation states and Europe's eyes were fixed on the region again. Fifty years after it first appeared, the text got a new life and its influence and resonance were even more powerful than decades back at the time of its original publication. West's book stirred a series of debates, induced polemics and provoked both appreciative and scathing commentaries. One thing is clear: whoever wanted to comprehend the causes of the new war in Europe consulted the monumental "key book about Yugoslavia"33 and sat down to read the "still one of the best introductions to the country and its people".34 In his "Introduction" to the new edition of the book published in 2006, Geoff Dyer compared West's style to that of Ryszard Kapuściński.35 The text originally fuelled by a fascination with the Balkans and the monarchical Yugoslavia came to be read in an entirely different context provided by the disintegration of the Titoan and Milosevicean Yugoslavia.

In the 90s, amidst the bloodshed of secession and deconstruction of Yugoslavia, a new revival of the "symbolic geography" took place,36 and the colonially underpinned discourse of Europe and the Balkans pitted against each other in a binary opposition was resumed. Rebecca West's book accrued new functions, becoming indisputably an important point of reference in the Balkan debate for the opponents of her viewpoints (who resented her Serbophilia and pro-Yugoslavian sentiments), her supporters and her fascinated followers alike. Cynthia Simmons aptly observes that the American influential journalist and analyst Robert Kaplan (1952)37 aspired in the 90s to play the role comparable to the one Rebecca West played during World War Two.38 He travelled across Yugoslavia with West's book in his hand and claimed that losing his passport would have been less of a problem and inconvenience to him than losing Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. The book he published in 1993 – Balkan Ghosts: A Journey Through History (Kaplan 1993) – as a result of his travel experiences was deeply influential. It stirred great interest in, among others, American president Bill Clinton, his wife Hillary Clinton and general Collin Powell, and, winning their appreciation, it indirectly affected the US Balkan politics in the 90s of the 20th century. Kaplan's book was interpreted in the categories of a report from a political journey, i.e. as travel journalism.39

Tony White's Another Fool in the Balkans: In the Footsteps of Rebecca West, 2006, is another example of the strong and suggestive influence of Rebecca West's book. On his journeys, White follows the route West took several decades earlier and produces a travel report covering the years 1993-2001. Although White's book is far shorter (254 pages), cannot boast any comparable profundity or poignancy, and falls short of West's intellectual allure, it undoubtedly testifies to the enduring and inspiring impact of the charismatic volume about Yugoslavia produced by Rebecca West, "a vast intellectual omnibus".40

In the 90s, Rebecca West's work was commented on and charted not only in political historical-philosophical and cultural frameworks. It also inspired feminist and gender-focused reflection bound up with "nostalgic nationalism"41 and was analysed in terms of genre theory as an example of female autobiography.42

Third Charting: 21st Century and Post-colonialism

Currently, we are witnessing a slow process in which defensive identities are constructed by colonised nations, tactics are devised to subvert the hegemonic discourse, and prejudices are exploded from within. In such context, the third charting of Black Lamb and Grey Falcon could involve taking post-colonial positions from which to venture beyond Western Orientalism and create a native discourse revolving around Rebecca West's opus magnum. In charting the book onto a new literary and paraliterary consciousness of various post-Yugoslavian nations now inhabiting new state structures, the text could open up to critical, perhaps also polemical, discussions which would articulate voices from within – intra muros – seeking to construct their own narratives around the book. That could greatly contribute to the efforts that many nations, so vividly described by West, invest in revising their self-perceptions and re-defining their identities. They would gain an increased opportunity to mark their respective narratives and exist as equal, distinct subjects side by side with others, no longer within the borders of one state. All this could not only enliven the representations of Yugoslavia of the late 30s, which West depicted with so much fascination, understanding and acceptance, but also expand the discourse on three Yugoslavias – the first, monarchical one, the second, socialist one and the third, nationalist one.

The first necessary step in this direction has been made – Rebecca West's book has appeared in two translations. The first, albeit abridged, translation was provided by a professor of English literature and a truly competent specialist, Nikola Koljević (1936–1997), who became a rather controversial political figure later. The second unabridged translation into Serbian of Rebecca West's monumental travel report Black Lamb and Grey Falcon appeared in 2004 and its author was Ana Selić. It was published more than 63 years after its original publication in English. It is only now, in the wake of the new, integral translation, that Black Lamb and Grey Falcon can be fully legitimately inscribed onto the literary map of several Balkan nations. One of the first texts to respond to the translation of Rebecca West's book into Serbian was an article by the Serbian journalist Stojan Cerović (1949–2005) titled "Rebeka Vest – Crno jagnje i sivi soko. Vek Jugoslavije" ("Rebecca West – Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. The Century of Yugoslavia"). The article appeared in the journal Vreme in 2004. and was reprinted in April 2013. to commemorate the 30th anniversary of Rebecca West's death. For Cerović, the monumental text is not only a hymn in praise of the South Slavic nations which has mutated into a requiem, or an exposition of multiple provoking issues about the condition of European civilisation, or, finally, a reckoning with the Western stereotypes of the Balkans. He highlights first of all the vision of Yugoslavia as an intricate and subtle compromise. Rebecca West's work serves him thus as a pretext for a contemporary reflection upon Serbia and hence provides a novel, polemical view. Another captivating offshoot in contemporary Serbia is a 'treatment'43 Rebecca West: Black Lamb and Grey Falcon (the film has not been made yet) published in the present issue of Knjiženstvo. It was authored by Srđan Koljević, a well-known director and the son of the book's first translator into Serbian. But more polemics, which now stands a chance of materialising, could unfold at the intersection of texts generated by particular nations portrayed in West's work and their self-perceptions and render outcomes interesting, hopefully, to all the parties involved. This post-colonial stage of charting the British writer's text in various countries of South-Eastern Europe is, however, still ahead of us.

Translated by Patrycja Poniatowska

[1] This text has been written within the framework of the project Knjiženstvo, Theory and History of Women’s Writing in Serbian until 1915: (No. 178029) of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Serbia

[2] Bakić-Hayden M., Hayden R.M., “Orientalist Variations on the Theme ‘Balkans’: Symbolic Geography in Recent Yugoslav Cultural Politics,”Slavic Review 51 (1992), p. 1–15; Kiossev A., “The Dark Intimacy: Maps, Identities, Acts of Identifications”,in: Balkan as Metaphor: Between Globalization and Fragmentation, D. I. Bjelić and O. Savić (eds.), Cambridge, Mass., London, England: The MIT Press, 2002, p. 165–190.

[3] I discussed it in more detail in: M. Koch, We and They – The Our and the Other. The Balkans of the 20th Century from a Colonial and Post-Colonial Perspective, Originally published in Porównania 6/2009, pp. 75–93. http://www.staff.amu.edu.pl/~comparis/attachments/article/225/10.Magdalena%20Koch.pdf

[4] Originally, „White man’s burden” was the title of Rudyard Kipling’s poem published in McClure’s Magazine in 1899, celebrating the American conquest of the Philippines and dedicated to queen Victoria. The phrase has since served as a vindication of the colonial enterprise as a humanitarian mission.

[5] The phrase is the title of a 1905 book authored by Edith Durham.

[6] Jezernik B., Wild Europe: The Balkans in the Gaze of Western Travellers, London: Saqi Books, 2004.

[7] Kitliński T., Obcy jest w nas. Kochać według Julii Kristevej, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Aureus, 2001.

[8] Todorova M., Imagining the Balkans, New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. In 1999, the book was translated into Serbian.

[9] Goldsworthy V., Inventing Ruritania: The Imperialism of the Imagination, New Heaven and London: Yale University Press, 1998. The Serbian translation of the book was published seven years later in Belgrade. Cf. V. Goldsvorti, Izmišljanje Ruritanije. Imperijalizam mašte, preveli sa engleskog V. Ignjatović i S. Simonović, Beograd: Geopoetika, 2000.

[10] Jezernik B., Wild Europe: The Balkans in the Gaze of Western Travellers, London: Saqi Books, 2004. The book was originally published in 1998 in the author’s native Slovenian.

[11] Novaković-Lopušina J., Srbi i jugoistočna Evropa u nizozemskim izvorima do 1918, Beograd: ReVision, 1999. The book’s impact and readership are smaller than those of the previous two, because it appeared only in Serbian. The author surveys five centuries (16th–20th ) of perception of the Balkans by representatives (politicians, diplomats, writers, travellers) of two minor European empires – the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Kingdom of Belgium.

[12] Bjelić D. I., SavićO. (eds.), Balkan as Metaphor: Between Globalization and Fragmentation, Cambridge, Mass., London, England: MIT Press, 2002, Blagojević J., Kolozova K., SlapšakS. (eds.), Gender and Identity: Theories from and/or on Southeastern Europe, Belgrade: Belgrade Women’s Studies and Gender Research Center, 2006.

[13] Bjelić D. I., SavićO. (eds.), Balkan as Metaphor: Between Globalization and Fragmentation, Cambridge, Mass., London, England: MIT Press, 2002.

[14] Longinović T. Z., “Vampires like Us: Gothic Imaginary and ‘the Serbs’”, in: Balkan as Metaphor. Between Globalization and Fragmentation, D. I. Bjelić and O. Savić (eds.), Cambridge, Mass., London, England: The MIT Press, 2002, p. 39–59.

[15] The writer’s mother did not approve of her daughter’s radical texts on moral, political and sexual themes, which she published in feminist journals The Free Woman and Clarion early in her career. The author adopted then a pseudonym borrowed from Ibsen: Rebecca West is the name of the protagonist of his Rosmersholm from 1886.

[16] Goldsworthy V., Inventing Ruritania: The Imperialism of the Imagination, New Heaven and London: Yale University Press, 1998, 172.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Glendinning V., Rebecca West: A Life, London: Papermac 1987.

[19] Selić A., Hronologija života i stvaralaštva Rebeke Vest,in: R. Vest, Crno jagnje, sivi soko. Putovanje kroz Jugoslaviju, s engleskog prevela A. Sanić, Beograd: MONO & MAÑANA, 2004, 877.

[20] West R., Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. A Journey through Yugoslavia, Edinburgh, New York and Melbourne: Canongate, 2006, 1088–89.

[21] West R., Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. A Journey through Yugoslavia, Edinburgh, New York and Melbourne: Canongate, 2006, 1126.

[22] Selić A., Hronologija života i stvaralaštva Rebeke Vest, in: R. Vest, Crno jagnje, sivi soko. Putovanje kroz Jugoslaviju, s engleskog prevela A. Sanić, Beograd: MONO & MAÑANA, 2004, 876.

[23] Stec L., “Female Sacrifice: Gender and Nostalgic Nationalism in Rebecca West’sBlack Lamb and Grey Falcon”, in: Narratives of Nostalgia, Gender and Nationalism, Jean Pickering and Suzanne Kehde (eds.), Macmillan, 1997, 138–158.

[24] Simmons C., “Baedeker Barbarism: Rebecca West’sBlack Lamb and Grey Falcon and Robert Kaplan’s Balkan Ghosts,” Human Rights Review, 10/01/2000, p. 109–125.

[25] West R., Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. A Journey through Yugoslavia, Edinburgh, New York and Melbourne: Canongate, 2006, 1092–1095.

[26] West R., Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. A Journey through Yugoslavia, Edinburgh, New York and Melbourne: Canongate, 2006, 7.

[27] Ibid., 1089.

[28] A black lamb was a sacrificial animal that Macedonian women who could not get pregnant and deliver a child offered on the feast of St. George (Đurđevdan).

[29] The gist of the story is that on the eve of the Battle of Kosovo (Kosovo Polje, literally Blackbirds’ Field), which took place on 28 June, 1389, prophet Elias came flying from Jerusalem as a grey falcon to the Serbian ruler, tsar Lazar, bearing a message from the Mother of God. She bid the monarch to choose for his people either „the heavenly kingdom” and the defeat or “the earthly kingdom” and the victory over the Turkish army. Tsar Lazar chose „the heavenly kingdom” for himself and his nation at the price of the lost battle and centuries of enslavement to the Turks.

[30] Selić A., Hronologija života i stvaralaštva Rebeke Vest,in: R. Vest, Crno jagnje, sivi soko. Putovanje kroz Jugoslaviju, s engleskog prevela A. Sanić, Beograd: MONO & MAÑANA, 2004, 878.

[31] Colquitt C., “A Call to Arms: Rebecca West’s Assault on the Limits of ‘Gerda’s Empire’ inBlack Lamb and Grey Falcon,” South Atlantic Review, 51(2), May 1986, 86.

[32] When Yugoslavia was invaded by the fascist, both the king and the government operated from their exile in Great Britain.

[33] Selić A., Hronologija života i stvaralaštva Rebeke Vest,in: R. Vest, Crno jagnje, sivi soko. Putovanje kroz Jugoslaviju, s engleskog prevela A. Sanić, Beograd: MONO & MAÑANA, 2004, 879.

[34] Dyer G., “Introduction”,in: R. West, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. A Journey through Yugoslavia, Edinburg, New York and Melbourne: Canongate, 2006, XV.

[35] Finder 1991, qtd. in Goldsworthy V, “Travel Writing as Autobiography: Rebecca West’s Journey of Self-Discovery”, in: Representing Lives. Women and Auto/biography, A. Donnell and P. Polkey (eds.), London: Macmillan Press Ltd, 2000, 88.

[36] Dyer G., “Introduction”, in: R. West, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. A Journey through Yugoslavia, Edinburg, New York and Melbourne: Canongate, 2006, XIV.

[37] Goldsworthy V., “Invention and In(ter)vention”,in: Balkan as a Metaphor. Between Globalization and Fragmentation, D. I. Bjelić and O. Savić (eds.), Cambridge, Mass., London, England: The MIT Press, 2002, 33.

[38] Robert David Kaplan (1952) is an American journalist, currently a National Correspondent for The Atlantic magazine and a writer for Stratfor. His writings have also been featured in The Washington Post, The New York Times, The New Republic, The National Interest, Foreign Affairs and The Wall Street Journal, among other newspapers and publications, and his more controversial essays about the nature of the US power have spurred debate in academia, the media, and the highest levels of government. Kaplan is the author of influential books: Surrender or Starve: The Wars Behind The Famine (1988) about Ethiopia, Soldiers of God: With the Mujahidin in Afghanistan (1990) about the Soviet-Afghan War in Afghanistan, Balkan Ghosts (1993) about The Balkans, and Warrior Politics: Why Leadership Demands a Pagan Ethos published shortly after 11.09.2001. He is the author of texts about Iraq and China. His latest book The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate (2012) describes how countries' respective political and social histories have been shaped by factors such as oceans and terrain features that form natural borders. In addition to his journalism, Kaplan has been a consultant to the U.S. Army's Special Forces, the United States Marines, and the United States Air Force. He has lectured at military war colleges, the FBI, the National Security Agency, the Pentagon's Joint Chiefs of Staff, major universities, the CIA, and business forums. When the Yugoslav Wars broke out, President Bill Clinton was seen with Kaplan's book Balkan Ghosts tucked under his arm, and White House insiders and aides said that the book convinced the President against intervention in Bosnia. Kaplan's book contended that the conflicts in the Balkans were based on ancient hatreds beyond any external control. Kaplan criticized the administration for using the book to justify non-intervention, but his popularity skyrocketed shortly thereafter along with demand for his reporting. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_D._Kaplan

[39] Simmons C., “Baedeker Barbarism: Rebecca West’sBlack Lamb and Grey Falcon and Robert Kaplan’s Balkan Ghosts,” Human Rights Review, 10/01/2000, p. 109–125.

[40] Ibid., 114.

[41] Chamberlain L., “Rebecca West in Yugoslavia,”Contemporary Review 248 (1444), May 1986, 264.

[42] Stec L., “Female Sacrifice: Gender and Nostalgic Nationalism in Rebecca West’sBlack Lamb and Grey Falcon”, in: Narratives of Nostalgia, Gender and Nationalism, Jean Pickering and Suzanne Kehde (eds.), Macmillan, 1997, p. 138–158.

[43] Goldsworthy V, “Travel Writing as Autobiography: Rebecca West’s Journey of Self-Discovery”,in: Representing Lives. Women and Auto/biography, A. Donnell and P. Polkey (eds.), London: Macmillan Press Ltd, 2000, p. 87–95.

[44] A piece of prose, typically written before the first draft of a screenplay.